- Home

- A. S. King

Everybody Sees the Ants Page 2

Everybody Sees the Ants Read online

Page 2

Granny Janice’s final breaths smelled like week-old oysters. She was pretty high on morphine and talking to herself. I didn’t know what to say, so I held her hand tightly and said, “Good-bye, Granny. I love you.”

Her fluttering eyelids lurched open, and she grabbed my forearm so hard that it left a red mark that outlived her. She said, “Lucky, you have to rescue my Harry! He’s still in the jungle being tortured by those damn gooks!”

“Gooks?” I asked.

“It’s the medicine, Lucky,” Mom whispered to me.

“You have to find him and bring him back! You need a father!” Granny blurted.

Then she died.

My mother sent me out of the room, which was fine by me, but she couldn’t erase those words from my memory. If Granny Janice needed me to do something, then I’d do it, even if I didn’t quite understand her orders.

Up until the cancer, Granny was my parent, I guess. When I was little, she’d watch me at her house while my parents worked. She’d sit at the kitchen table making phone calls and doing paperwork all day while I played with all of the cool old toys in her toy box. One time she told me that she wished I could live with her. I remember thinking that would be nice. Before she got cancer, the school bus would drop me at her door, and she would help me with my homework and feed me dinner until my mom would pick me up at six. It was just the way things were, and I liked it that way.

Dad’s eyes were red, and he put his face in his hands. I picked up my Transformers and moved to the sunroom, and while Mom and Dad made the calls they had to make, I went straight to work.

I renamed Optimus Prime “Gook” and shifted an overgrown houseplant into the corner to make a jungle. I went to Granny Janice’s toy box and dug out a small doll that had come with a farm set—a farmer in a hat, missing one leg after I’d bent it too far backward the previous Christmas—and I buried him to his waist in the houseplant soil and called him “Harry.” While the coroner came and removed the body and helped my parents fill out paperwork, I rescued Harry from Gook about twenty times (by helicopter, riverboat, waterfall, ambush) before it was finally time to leave.

On our way home we stopped at a small neighborhood bar and grill and ate hamburgers in silence. Dad was just eating what he could, which wasn’t much, and the only thing Mom could do was point out the train set that was suspended above the middle of the dining room, as if I were five. I swear, she nearly called it a choo-choo. I decided to go to the bathroom to escape.

I didn’t really have to pee, but I went through the motions at the urinal anyway. About a minute after I got there, Nader McMillan came in and stood at the neighboring urinal. He was seven like me, but a lot taller (though that wouldn’t be difficult). He peed like he’d been holding it in for a week. It splashed off the urinal and the little lemon-shaped disk at the bottom. I felt some splash-back hit my arm, but I didn’t say anything because I knew Nader from first-grade recess and knew he was mean. I just stood there, little penis in hand, aiming but not peeing, praying he wouldn’t notice me.

“What are you looking at?” he asked, even though my eyes hadn’t moved. He turned toward me and peed on my sandals. On my feet. On my shins.

I didn’t say anything and neither did he. He shook and zipped back up and didn’t wash his hands before he left. I stood motionless, nervously wiggling my floppy tooth with my tongue until he was gone. Then I zipped myself and squished over to the sink. My feet felt disgusting, and I was debating whether to take off my sandals and wash them, when my dad and the manager came in. They looked at the pee puddle on the terracotta-tiled floor.

“Christ, Lucky,” Dad said.

The manager said, “Doesn’t look like an accident to me, man.” He opened a small closet door to the right of the urinals and retrieved a mop, a bucket and a stand-up yellow plastic sign that read WET FLOOR.

“It wasn’t me,” I said. “It was that Nader kid.”

Dad looked at the manager and said, “Really—he’s a good kid.”

“I’m sure he is. But Mr. McMillan is a regular patron here, and his kid said he saw your son doing it.”

I shook my head and started to cry.

Five minutes later we were driving home, silent, with Styrofoam carriers on our laps. As we drove through Frederickstown toward our little suburban development, I watched the big houses on Main Street pass by and I twisted my loose tooth right out of my jaw. Looking back, I guess that was the day that changed everything.

JUNGLE DREAM #1

I was walking alone on a path. I was in my Spider-Man pajamas and red Totes slippers. The jungle was loud with birdcalls and the zeep-zeep-zeep-zeep of insects. I looked down a lot, like a kid does in a big place. I focused on the bugs and the fallen leaves rather than looking up at the enormous canopy and the vines and the endlessness of it all.

When I came to a stream, I looked for rocks so I could cross it. I saw my red fleece slipper reach out for the first flat rock, and I saw it slide, and felt myself go off balance, until I was wet, bottom first, in the stream.

“Here, son,” someone said in a hushed and husky voice. I looked up, and there was a skinny man with a bushy gray beard holding his hand out to me. “Come on. No sense crying. You’ll be dry in no time.”

I took his hand and he helped me cross to the other side. When I got there, he looked me up and down. “Those are very cool pajamas. I wish Frankie could get me a pair with Spider-Man on the front.” He wore a pair of thinning black pajamas that stopped mid-shin, and was barefoot. His feet were a mess of sores and scars.

“Who are you?” I asked. “And who’s Frankie?”

The man cocked his head to the side and studied me some more, stroked his beard with his right hand and smiled. “Don’t you worry about that,” he said. “Follow me and we’ll dry those pajamas.” He walked to a sparkling clearing of sun rays, and I followed, the water squishing through my toes in my Totes.

Halfway there, a mean-looking Asian man in a worn uniform jumped out of a thatched bamboo hut. He pointed a rifle at me and yelled, “Lindo-man, who the kid?”

• • •

I woke up instantly, still wet, and screaming. Mom was standing over me, shaking me awake. “It’s just a bad dream,” she said. “It’s just a bad dream.”

It was two in the morning. Mom was tiptoeing around because she didn’t want to wake Dad, who had to get up in only a few hours to go to work at his new chef job. She said, handing me a pair of dry pajamas, “Just put these on. Don’t worry. Accidents happen.” I was still half inside the dream, hearing those final words that woke me. Lindo-man, who the kid?

Linderman.

Linderman.

It was Granddad. The man I was supposed to rescue. I’d found him.

RESCUE MISSION #1—A WEEK LATER

This time, as I walked toward the stream, I saw other things on the path. I saw little traps—holes dug with leaf cover to sprain an ankle in. Before I came to the clearing where the stream was, I found a group of spikes and poked them with a stick. I continued to push them until the square bit of wood lay on its side, revealing the six-inch-long nails that were hammered through it. I couldn’t be sure, but there was something smeared all over the nails, and I think it was poop.

I crossed the stream without falling in and came to the bamboo huts outside the fenced-in area. The sounds of the jungle were deafening this time. Like when the cicadas come in Pennsylvania, except it wasn’t familiar. It was all wild and scary.

“Psst.”

I looked around but couldn’t see who was making the noise.

“Kid! Look up!”

I looked up and there he was, the skinny man with the beard, sitting on a long branch of a tree. He was cross-legged, though it seemed physically impossible that he could sit that way on a tree branch, and he beckoned to me.

I eyed the trunk of the tree. There was no way I could get up. “How’d you get up there?” I asked.

“It’s a dream, son. You can go anywhere you want.”<

br />

So I closed my eyes and put myself in the tree next to him. We stared at each other. He sat up tall, his back straight, and smiled.

“Why are you up a tree?” I asked.

“Because it’s better than not being up a tree.”

“I saw the spikes,” I said, thinking that’s what he must have meant—that being up a tree was safer than being on the ground.

“The what?”

“The spikes. You know—the nails in the ground?”

He acknowledged what I meant. “Oh! Charlie’s booby traps! Gotcha.”

“Who’s Charlie?”

He reached out and patted my hand. “Never you mind, son. It’s nothing you need to worry about.”

Somehow, right then I knew for sure this really was my grandfather. I looked at him and could see my dad’s face in his face. I could see my face, too. It was a trustworthy face.

“Granddad?”

“Yeah?”

“What do I do about Nader McMillan?”

“Who’s that?” he asked.

“The kid who peed on my feet. He’s mean to everybody.”

“A bully?”

“Yeah,” I said. “A big one.”

The old man thought for a minute. “Do you know what my mother told me to do to bullies?”

“No.”

“She told me to ignore them. I think you should ignore that kid, too.”

“But he peed on me.”

He rubbed his chin through his beard. “He may have peed on your feet, but nobody can pee on your soul without your permission.”

I had no idea what this meant.

“What if ignoring him doesn’t work?”

“Then you get back to me. We’ll figure it out together.”

“Okay,” I said, and glanced toward the camp below. I took note of the huts, some abandoned, some in use. “Is this a camp?” I asked.

“Yes. A prison camp.”

My eyes moved to the barbed-wire fence surrounding a larger thatched hut. “Prison camp?”

He nodded.

“So you’re a bad guy? A robber or something?”

He exhaled and let his straight back curve. “No, son. I’m not a bad guy.”

I looked around the jungle and down at the prison camp. “So why are you here?”

He laughed as if he might be crazy or happy or something. When he was done, he said, “My number came up.”

I shook my head.

“The lottery, Lucky. They picked my number and drafted me. A year later I was in Vietnam fighting in a war. A year after that I was a prisoner of war, and a year after that they started moving me around to places like this.”

“Because of a number?” This did not mesh with my idea of a lottery. I’d watched those five-minute Powerball lottery shows with my mom. I was pretty sure nobody went to war because of the Ping-Pong balls with numbers on them.

“Yep. Number fourteen.” He put a small green twig in his mouth and scraped each remaining tooth clean. “Each day of the year was assigned a number. March first, my birthday, was assigned number fourteen. Got it?”

I didn’t get it. Not at all.

“Well, don’t cry, son. There’s nothing we can do about it now.” He put his arm around me, and the two of us switched positions. We sat on the branch, hugging each other, our legs swinging, me sobbing into the old man’s chest.

After a minute of this, Granny’s voice came back to me, and I remembered why I was there. I wiped my tears on his shirt and looked him square in the eye.

“I’m getting you out of here, Granddad,” I said. “I’m going to bring you home.”

THE THIRD THING YOU NEED TO KNOW—THE TURTLE

When we get home from the pool, I am still totally preoccupied by the Charlotte Dent bikini-top incident and the last thing Nader said to me. You’re mine, Linderman. God, what a dick.

We walk in the back door and Dad is in the kitchen, stirring sugar into a pitcher of fresh iced tea and humming a Bruce Springsteen song.

“You want two or three ears of corn?” He asks this as if the whole scene is normal. Him here, cooking dinner, being my dad. Being present.

“Two, please.”

I go into my room and change out of my pool stuff. I sit on my bed and think about Nader McMillan and wonder what I’m going to do. Ignore him. Stand up to him. Avoid him. Be “tough.” I think of the stuff Dad has said over the years. How he finally gave up suggesting things. Why are you asking me this? I never figured out what to do about my own bullies. How am I supposed to know what to do with yours?

I tried all of his ideas. I even tried a few he never suggested. I tried sucking up to Nader and being his friend, which only worked for a little while during freshman year until I got him in trouble with the questionnaire. I tried talking to one of the guidance counselors last January, only to hear that Nader is a pain, yes, but the best thing to do is stay out of his way. “He’s probably a good kid underneath it all,” the counselor said. Which isn’t true. But it meant Nader could keep treating kids like that, charming all the teachers with his perfect, whitened smile, and still play baseball in the spring. And it meant his lawsuit-happy lawyer father would stay off the school district’s back.

“Lori, you ready to eat?” Dad yells.

She answers, “Two minutes!”

“Lucky! Do your business and wash your hands,” he says. It’s as if since my dad started working in Le Fancy-Schmancy Café, he thinks I stopped growing. I’m not seven anymore. I know when I need to pee.

When I sit at the table, they are both smiling at me and I frown. My father starts dishing out portions of barbecued honey-and-fresh-herb-marinated chicken and grilled, peppered corn on the cob. He points to the bowl of buttery, parsley-sprinkled new potatoes on the table and says, “Help yourself.”

This is a normal meal, considering it’s usually lightly seared chicken medallions glazed with blackberry sauce or stuffed with foie gras, or pork chops breaded with organic mushroom dust and served with petits pois peas smothered in garlic and almond butter, with a dash of lime. I don’t know where he gets this from. Granny Janice was fond of Spam, macaroni and cheese out of a box and grilled cheese sandwiches.

While I’m halfway through my second ear of corn, Mom says, “Lucky helped a girl at the pool today. It was very sweet.”

Dad looks at me and nods his head. “Proud of you.”

“Do you want to tell him what else happened?” Mom asks.

“Nah.” I’m not even sure what she’s talking about, but I think it’s Nader being an asshole. How is this news?

“What happened?” he asks.

“It was nothing,” I say, diving back into my ear of corn.

“He got pushed around by that McMillan boy again,” she says.

“I perfected the cannonball, too. You should see it,” I say.

“Did you push him back?”

I pretend we’re not talking about this. “Huh?”

Mom says, “The McMillan boy. He wants to know if you pushed back.”

“No.”

“Good. Fighting is for sissies,” he says.

I wish I could tell him how much I disagree.

I wish he would fight himself and win me.

But that’s the thing, isn’t it? The thing about my dad? There’s no point in disagreeing with him because he already does it all by himself. Here’s an example.

Have you ever seen those POW/MIA flags? The black ones with the soldier and the guard tower, with the words YOU ARE NOT FORGOTTEN across the bottom, like this?

We have them plastered all over our cars, our windows, our stuff—my baseball bat and Mom’s bird feeders. We have a flagpole in the front yard where we fly the biggest POW/MIA flag that will fit. My father sews a patch on my winter coat every year. And my swimming trunks. And my gym uniform. I have exactly fourteen different POW/MIA T-shirts. He has it tattooed on his right arm, has a license plate holder, a set of coasters, mugs and playing cards.

In our house

the slogan rings true. There is no way to forget our missing heroes here. No way. But we never really talk about it.

And then he says, “Fighting is for sissies.”

Some days I want to tie the two of them to the sofa and speak my mind. Say stuff. Real stuff. Ask stuff. How come we gave up on Granddad when Granny Janice died? Why did she ask me to rescue him? Why didn’t she ask you? And why aren’t we doing something? Anything?

The only real thing I ever heard Dad say was, “It would have been better if my dad had come home in a bag, because then at least we would know.” Then he transforms into a turtle.

Of course, the shell is the biggest part of a turtle.

And we never really talk about it.

OPERATION DON’T SMILE EVER—FRESHMAN YEAR

The day after Evelyn Schwartz went blabbing to the guidance office about my suicide survey, Danny and Nader got a lecture from the principal. I know this because Danny told me on the bus home from school.

“Why’d you have to ruin our joke?”

“I didn’t think it was a big deal,” I said.

“Fish says he’s going to call my dad, man.” We called the principal, Mr. Temms, “Fish” because his eyes bulged and his head was flat.

“Why?”

“You know why. They’re all retards, that’s why.”

“Huh,” I said.

“And Nader is pissed,” he added.

“Him too?”

“We got called down together,” he said. “To check out your stupid little story.”

“Shit.”

“Yeah, shit. Nader’s dad will flip out, too.”

“I’m really sorry,” I said. “I didn’t think it was that big of a deal.”

“Once Nader finds you, you’ll be way sorrier.”

“You think?”

“The guy’s a maniac.”

“Yeah, but we’re—kind of friends now, aren’t we?”

He laughed and shook his head. “Not anymore, you’re not.”

Still Life With Tornado

Still Life With Tornado Ask the Passengers

Ask the Passengers Glory O'Brien's History of the Future

Glory O'Brien's History of the Future I Crawl Through It

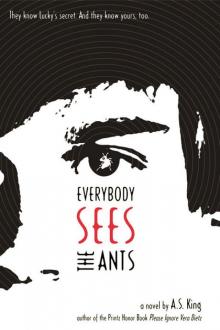

I Crawl Through It Everybody Sees the Ants

Everybody Sees the Ants The Dust of 100 Dogs

The Dust of 100 Dogs The Quest for Hope | Christian Fantasy Adventure (Invisible Battles Book 1)

The Quest for Hope | Christian Fantasy Adventure (Invisible Battles Book 1) The Quest for Hope | Christian Fantasy Adventure

The Quest for Hope | Christian Fantasy Adventure Reality Boy

Reality Boy Please Ignore Vera Dietz

Please Ignore Vera Dietz